|

|

|

| Home | More Articles | Join as a Member! | Post Your Job - Free! | All Translation Agencies |

|

|||||||

|

|

Velar consonant

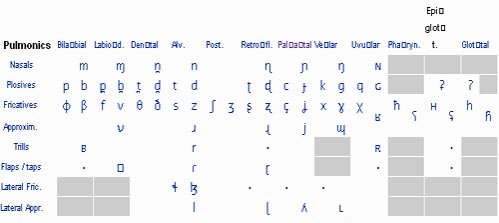

Velars are consonants articulated with the back part of the tongue (the dorsum) against the soft palate (the back part of the roof of the mouth, known also as the velum). Since the velar region of the roof of the mouth is relatively extensive and the movements of the dorsum are not very precise, velars easily undergo assimilation, shifting their articulation back or to the front depending on the quality of adjacent vowels. They often become automatically fronted, that is partly or completely palatal before a following front vowel, and retracted before back vowels. Palatalised velars (like English /k/ in keen or cube) are sometimes referred to as palatovelars. Many languages also have labialized velars, such as [kʷ], in which the articulation is accompanied by rounding of the lips. There are also labial-velar consonants, which are doubly articulated at the velum and at the lips, such as [k͡p]. This distinction disappears with the approximant [w], since labialization involves adding of a labial approximant articulation to a sound, and this ambiguous situation is often called labiovelar. The velar consonants identified by the International Phonetic Alphabet are:

It is important to note at this point that a velar trill or tap is not possible - see the shaded boxes on the consonant table at the bottom. In the velar position the tongue has an extremely restricted ability to carry out the type of motion associated with trills or taps. Nor does the body of the tongue have the freedom to move quickly enough to produce a velar trill or flap.[3]

Lack of velarsThe velar consonant [k] is the most common consonant in human languages.[4] Nonetheless, there are languages which lack simple velars. An areal feature of the Pacific Northwest coast is that historical *k has become palatalized in many languages, in many languages becoming [kʲ], but in others, such as Saanich, Salish, and Chemakun becoming [tʃ]. (Likewise, historical *k’ has become [tʃʼ] and historical *x has become [ʃ]; there was no *g or *ŋ.) However, all three languages retain a labiovelar series [kʷ], [kʼʷ], [xʷ], [w], as well as a uvular series. Apart from [ɡ], none of the other velars are particularly common, not even [w] and [ŋ], which occur in English. [ɡ] of course does not occur in languages like Mandarin Chinese which lack voiced stops, but it is sporadically missing elsewhere. About 10% of languages which otherwise have [p b t d k ɡ], such as Standard Arabic, are missing [ɡ].[5] The Pirahã language has both a [k] and a [ɡ] phonetically. However, the [k] does not behave as other consonants, and the argument has been made that it is phonemically /hi/, leaving Pirahã with only [ɡ] as an underlyingly velar consonant. Hawaiian does not distinguish [k] from [t]; the sound spelled k tends toward [k] at the beginnings of utterances, [t] before [i], and is variable elsewhere, especially in the dialect of Niʻihau and Kauaʻi. Since Hawaiian has no [ŋ], and w similarly varies between [w] and labial [v], it's not clear that it is meaningful to say that Hawaiian has velar consonants. Notes

References

See also

This table contains phonetic

information in IPA,

which may not display correctly in some browsers.

Published - November 2008 Information from Wikipedia

is available under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation

License

E-mail this article to your colleague! Need more translation jobs? Click here! Translation agencies are welcome to register here - Free! Freelance translators are welcome to register here - Free! |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Legal Disclaimer Site Map |