|

|

| Advertisements |

|

|

|

The Arabic Language and Folk Literature. A call for gathering and translating Arab folk tales.

By Srpko Lestaric

srpkole@EUnet.yu

Become a member of TranslationDirectory.com at just

$12 per month (paid per year)

A long time ago, during my first days spent in

Arab countries, I noticed—as did everyone from the Arabic

translators' tribe—the great importance of knowing the

colloquial language of the region (al-'arabiyya al-'aammiyya,

or al-lugha ad-daarija).

Diglossia in Arabic is almost indescribable.

Numerous vernaculars are related to classical Arabic (al-'arabiyya

al-fushaa) in the same way as modern Romance languages are

related to Latin, and they differ from each other as much

as these latter languages differ from each other. Most people

understand you when you speak fusha, "modern standard

Arabic" (SA—American academics usually use the acronym

MSA), but then you sound ridiculous (people smile and even

laugh), because nobody uses it in speech, except in certain

formal situations. It is almost solely the language of writing

and only the educated can use it in oral communication with

some ease. It is not a mother tongue, but nevertheless it

is taught in schools (B. F. Grimes: Ethnologue—Languages

of the World, SIL, Dallas, 13th ed. 1996). Diglossia in Arabic is almost indescribable.

Numerous vernaculars are related to classical Arabic (al-'arabiyya

al-fushaa) in the same way as modern Romance languages are

related to Latin, and they differ from each other as much

as these latter languages differ from each other. Most people

understand you when you speak fusha, "modern standard

Arabic" (SA—American academics usually use the acronym

MSA), but then you sound ridiculous (people smile and even

laugh), because nobody uses it in speech, except in certain

formal situations. It is almost solely the language of writing

and only the educated can use it in oral communication with

some ease. It is not a mother tongue, but nevertheless it

is taught in schools (B. F. Grimes: Ethnologue—Languages

of the World, SIL, Dallas, 13th ed. 1996).

Naturally, the tales Arab grandmothers tell children are anything

but examples of SA. I tried to find some of these tales, knowing

that they would help me a great deal to learn the language

of everyday speech. But, lo and behold—there were no

such books. Absolutely none. Not in Damascus, Baghdad, Amman,

Kuwait, or Cairo—nowhere!

Year after year I was greatly amazed to find out that throughout

the Arabs' homeland there was not a single compilation of

folk tales written in their original dialects and published

for general audience reading.

As an admirer of folk traditions, I was badly disappointed.

There are only a few collections prepared for scientific purposes

and a few others compiled by non-Arabs and translated into

English, German or Russian. I do not count those that are

stylized or, rather, translated into SA, which are numerous;

they are not authentic, no matter how very beautiful, important

and strongly expressive SA is in itself.

It is obvious that neither the ideology of Pan-Arabism nor

the Islamic dogma favors any attempt to promote spoken dialects.

In some Arab countries printing a story or a novel (plays

and poems excepted) in the "vulgar language" is

nowadays against the law. Extremely dogmatic people will even

tell you that there is no such a thing as Arabic dialects!

They believe that publishing original tales would jeopardize

the Arabs' unity. However, in their homes and in the streets,

these very people speak in dialect only.

On the other hand, it is clear to everyone that Arab folktales

do exist as they always have existed and that they must be

something special, bearing in mind the glorious cultural heritage

of the Arabs enriched by Persian and Indian influences. I

myself have gathered some of them and was enchanted. Little

children all over the world—and the children hidden in

all of us grown-ups as well—ought not to be prevented

from reading them.

In the last two or three decades the Arabs themselves have

started, at a slow pace, to take care of their lore in the

field of oral literature. Article 7 of the Final Recommendations

of the Arab Folklore Symposium held in March 1977 in Baghdad

reads: "Encouragement of translating vital selections

of the Arab folklore into foreign languages and publishing

them all over the world for the purpose of greater divulgation

and to help prevent plagiarism and falsification." But

there are still no books of original folk tales in Arab bookstores

or libraries.

In order to familiarize the peoples of the former Yugoslavia

with these treasures, some years ago I translated into Serbo-Croatian

and published a compilation of 35 Arab folk tales from Jerusalem,

recorded by Enno Littmann (Modern Arabic Tales, Leiden, 1905)

from the mouth of a gifted Arab named Selim Ga'anine, whose

name is now unfortunately forgotten. The title of the book

was An Anthology of Arab Folktales (published by "Vreme

knjige", Belgrade, 1994).

It took me many years until I had a good pile of such authentic

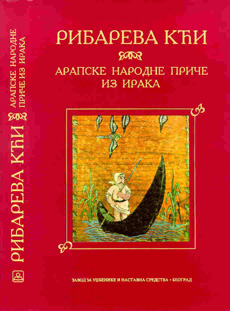

tales in my hands. My second book of the kind, entitled Ribareva

kci ("The Fisherman's Daughter," published by

"Zavod za udzbenike", Belgrade, 1998), contains

40 tales (sawaalif sha'biyya) from Mesopotamia, plus 24 anecdotes,

all told in the lively Arabic vernaculars of Waadi ar-Raafidayn.

This book is my own compilation, based on research in archives,

old periodicals and museums, not on fieldwork.

Both of these translations use a kind of language that sounds

somewhat "dialectal" and slightly archaic, although

it is actually based on modern urban speech. I gave them the

final touch by reading each translated tale aloud in the "epic"

way used in telling tales to children.

The Fisherman's DaughterAnthology, is a book of

about 320 pages, including an extensive study on the relationship

between SA and "al-'aammiyya." The book has its

Arabic part too: a detailed table of contents with the full

names of the tellers and compilers, one complete tale in the

Arabic script, its full scientific transliteration (for students

of Arabic), and information about my work in this field.

The font used for the above-mentioned transliteration is composed

in accordance with the ZDMG system.

Here we come to a matter which is of utmost importance, in

my opinion. It is my appeal to every Arab in the world to

send me as many Arab dialectal folk tales as he/she can, written

or taped, for my further work. This appeal is found in the

book itself, but it is of little help as our publisher cannot

even afford to put it on the Web—let alone send twenty

or thirty copies of the book to scholars abroad.

As far as folk tales are concerned, "translations"

into SA are absolutely outside my interest. (I already have

hundreds of them.) Only authentic tales in their original

dialects—mainly eastern ones—are called for. For

further information contact me at any time by e-mail or at

the following address:

Srpko Lestaric

11080 Zemun, Yugoslavia, Dobanovacka 83

Phone: (++381-11) 10 30 15 home (after 4 p.m. Western European

time)

311 2743 Office

Thanks in advance.

This article was originally published at Translation Journal (http://accurapid.com/journal).

Submit your article!

Read more articles - free!

Read sense of life articles!

E-mail

this article to your colleague!

Need

more translation jobs? Click here!

Translation

agencies are welcome to register here - Free!

Freelance

translators are welcome to register here - Free!

|

|

|

| Free

Newsletter |

|

|

|

|

|