|

|

|

| Home | More Articles | Join as a Member! | Post Your Job - Free! | All Translation Agencies |

|

|||||||

|

|

Consonant

In articulatory phonetics, a consonant is a speech sound that is articulated with complete or partial closure of the upper vocal tract, the upper vocal tract being defined as that part of the vocal tract that lies above the larynx. Consonants contrast with vowels. Since the number of consonants in the world's languages is much greater than the number of consonant letters in any one alphabet, linguists have devised systems such as the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) to assign a unique symbol to each attested consonant. In fact, the Latin alphabet, which is used to write English, has fewer consonant letters than English has consonant sounds, so digraphs like "ch", "sh", "th", and "zh" are used to extend the alphabet, and some letters and digraphs represent more than one consonant. For example, many speakers are not aware that the sound spelled "th" in "this" is a different consonant than the "th" sound in "thing". (In the IPA they are transcribed ð and θ, respectively.)

Origin of the termThe word consonant comes from Latin oblique stem cōnsonant-, from cōnsonāns (littera) "sounding-together (letter)", a loan translation of Greek σύμφωνον sýmphōnon.[1] As originally conceived by Plato,[2] sýmphōna were specifically the stop consonants, described as "not being pronounceable without an adjacent vowel sound".[3] Thus the term did not cover continuant consonants, which occur without vowels in a minority of languages, for example at the ends of the English words bottle and button. (The final vowel letters e and o in these words are only a product of orthography; Plato was concerned with pronunciation.) However, even Plato's original conception of consonant is inadequate for the universal description of human language, since in some languages, such as the Salishan languages, stop consonants may also occur without vowels (see Nuxálk), and the modern conception of consonant does not require cooccurrence with vowels. Consonantal featuresEach consonant can be distinguished by several features:[4]

All English consonants can be classified by a combination of these features, such as "voiceless alveolar stop consonant" [t]. In this case the airstream mechanism is omitted. Some pairs of consonants like p::b, t::d are sometimes called fortis and lenis, but this is a phonological rather than phonetic distinction.

Consonant as a symbolThe word consonant is also used to refer to a letter of an alphabet that denotes a consonant sound. Consonant letters in the English alphabet are B, C, D, F, G, H, J, K, L, M, N, P, Q, R, S, T, V, X, Z, and usually W and Y: The letter Y stands for the consonant [j] in "yoke", and for the vowel [ɪ] in "myth", for example; W is almost always a consonant except in rare words (mostly loanwords from Welsh) like "crwth" "cwm". Consonants and vowelsConsonants and vowels correspond to distinct parts of a syllable: The most sonorous part of the syllable (that is, the part that's easiest to sing), called the syllabic peak or nucleus, is typically a vowel, while the less sonorous margins (called the onset and coda) are typically consonants. Such syllables may be abbreviated CV, V, and CVC, where C stands for consonant and V stands for vowel. This can be argued to be the only pattern found in most of the world's languages, and perhaps the primary pattern in all of them. However, the distinction between consonant and vowel is not always clear cut: there are syllabic consonants and non-syllabic vowels in many of the world's languages. One blurry area is in segments variously called semivowels, semiconsonants, or glides. On the one side, there are vowel-like segments which are not in themselves syllabic, but which form diphthongs as part of the syllable nucleus, as the i in English boil [ˈbɔɪ̯l]. On the other, there are approximants which behave like consonants in forming onsets, but are articulated very much like vowels, as the y in English yes [ˈjɛs]. Some phonologists model these as both being the vowel /i/, so that the English word bit would phonemically be /bit/, beet would be /bii̯t/, and yield would be phonemically /i̯ii̯ld/. Similarly, foot would be /fut/, food would be /fuu̯d/, wood would be /u̯ud/, and wooed would be /u̯uu̯d/. However, there is a (perhaps allophonic) difference in articulation between these segments, with the [j] in [ˈjɛs] yes and [ˈjiʲld] yield and the [w] of [ˈwuʷd] wooed having more constriction and a more definite place of articulation than the [ɪ] in [ˈbɔɪ̯l] boil or [ˈbɪt] bit or the [ʊ] of [ˈfʊt]. The other problematic area is that of syllabic consonants, that is, segments which are articulated as consonants but which occupy the nucleus of a syllable. This may be the case for words such as church in rhotic dialects of English, although phoneticians differ in whether they consider this to be a syllabic consonant, /ˈtʃɹ̩tʃ/, or a rhotic vowel, /ˈtʃɝtʃ/: Some distinguish an approximant /ɹ/ that corresponds to a vowel /ɝ/, for rural as /ˈɹɝl/ or [ˈɹʷɝːl̩]; others see these as the a single phoneme, /ˈɹɹ̩l/. Other languages utilize fricative and often trilled segments as syllabic nuclei, as in Czech and several languages in Congo and China, including Mandarin Chinese. In Mandarin, they are historically allophones of /i/, and spelled that way in Pinyin. Ladefoged and Maddieson[4] call these "fricative vowels" and say that "they can usually be thought of as syllabic fricatives that are allophones of vowels." That is, phonetically they are consonants, but phonemically they behave as vowels. Many Slavic languages allow the trill [r̩] and the lateral [l̩] as syllabic nuclei (see Words without vowels), and in languages like Nuxalk, it is difficult to know what the nucleus of a syllable is (it may be that not all syllables have nuclei), though if the concept of 'syllable' applies, there are syllabic consonants in words like /sx̩s/ 'seal fat'. Common consonantsMany consonants are far from universal. For instance, most Australian languages lack fricatives; a large percentage of the world's languages, for example Mandarin Chinese, lack voiced stops such as [b], [d], and [g]. The most common consonants around the world are the voiceless plosives [p], [t], [k] and the nasals [m], [n] (but not [ŋ]). Most languages also include one or more liquid consonants, with [l] the most common, and one or more semivowels, usually [j] and/or [w]. However, even these are not universal. Several languages lack any approximants, such as Nama and Naasioi. Several languages in the vicinity of the Sahara Desert, including Arabic, lack [p]. Several languages of North America, such as Mohawk, lack the labials [p] and [m]. A few languages on Bougainville Island and around Puget Sound, such as Makah, lack the nasals [m] and [n]. Colloquial Samoan lacks the alveolars [t] and [n].[5] The lack of a [t] has only been reported for Samoan and perhaps some dialects of Hawaiian, as well as Nǀu, and the few languages which do not have a simple [k] sound have a consonant that is very close. For instance, an areal feature of the Pacific Northwest coast is that historical *k has become palatalized in many languages, so that Saanich for example has [tʃ] in place of [k], but it does retain [kʷ] and[q].[6][7] Xavante is reported as having no dorsal stops whatsoever, but does have [tʃ]. Hawaiian is remarkable in having free variation between [t] and [k].[8] The most frequent consonant (that is, the one appearing in vocabulary most often) is in several languages [k]. See also

References

External links

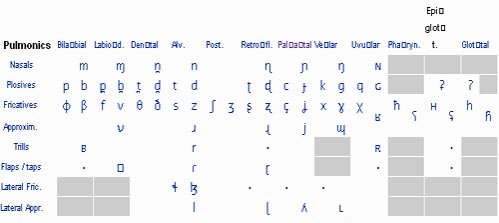

This table contains phonetic

information in IPA,

which may not display correctly in some browsers.

Published - November 2008 Information from Wikipedia

is available under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation

License

E-mail this article to your colleague! Need more translation jobs? Click here! Translation agencies are welcome to register here - Free! Freelance translators are welcome to register here - Free! |

|

|

Legal Disclaimer Site Map |