|

|

|

| Home | More Articles | Join as a Member! | Post Your Job - Free! | All Translation Agencies |

|

|||||||

|

|

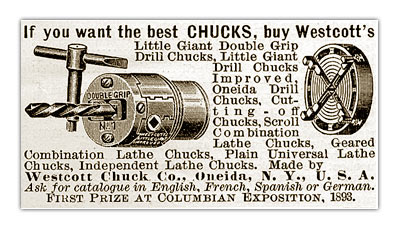

The Digital Divide - Why Localization Matters More Than We Know

In a recent article in Scientific American entitled “Demystifying the Digital Divide,” Mark Warschauer of the University of California, Irvine reports on the failure of attempts to eliminate the “Digital Divide,” the differential rates in access to high-technology products and services between groups and locations around the world. According to the article, many attempts to eliminate this differential have focused on provision of hardware, letting users discover for themselves what computers can do. However, without explicit education in computer use, most children and other potential users never learn how to really use computers. Recounting one experiment in India, Warschauer states, “…without educational programs and with the content primarily in English rather than Hindi, they mostly did what you might expect: played games and used paint programs to draw.” Despite inspirational stories about poor children who have taught themselves to use computers and have improved their lives, mere hardware provision generally does not lead to computer literacy. In contrast, other attempts that have focused on the context within which computer services are accessed, as well as educating the populace about computer usage, have obtained more success. In particular Warschauer cites a project called Gyandoot (“purveyor of knowledge”) in Madhya Pradesh, one of the poorest states in India. In the Gyandoot project, villages are provided with a single computer that can access the Gyandoot network. This computer is operated by a local entrepreneur, who can charge for computer usage time. (The local operator is important because many of the users are illiterate and need assistance to understand the information they obtain). The project is self-sustaining because of the access fees (a few cents per access), and requires minimal governmental support compared to the computer kiosks in the other project. Gyandoot allows villagers to access information on crop prices (saving long trips to market towns), governmental programs, and so forth, and has also improved governmental services since villagers have an easy method of communicating with the state government concerning problems such as broken water pumps or problems with schools. The program does not seek to provide access to all sorts of content available on the Internet, but rather to utilize digital technology to address a limited set of community needs in Madhya Pradesh. In hindsight, it is almost pointless to ask why the first example fails to work, while Gyandoot does seem to work, but the answer may not be as simple as it seems. Aside from the lack of education inherent in the first example, the real failure seems to be lack of localization. I don’t mean just adaptation of textual and non-textual material here, but real adaptation of a service to meet local needs. Gyandoot succeeds because it adapts computer access to the needs and realities of a locale, whereas the first program fails to localize the services to match the needs of any locale (it even fails to provide linguistically-acceptable materials). What we really see is that without thorough localization computers are essentially expensive and pointless toys. It is also worth noting that the “traditional localization” component of this sort of localization is fairly minimal. Because the service is limited to addressing locale-specific needs such as finding crop prices, there is very little translation involved, and most of the content is developed and consumed locally (and would, indeed, be worthless outside of the Madhya Pradesh locale). However, this localization relies on years of traditional localization that has now descended to the level of infrastructure. Without the work of localizers in the past who developed Hindi-enabled systems and applications, without Devanagari font developers, and without the technical expertise of this industry, the Gyandoot project would not be possible. Sometimes we have to wonder whether what we do makes a difference in the grand scheme of things when 95% of what we do is obsolete within a year. We are stuck in a cycle in which our localizations are intended to be worthless within a few years (as, indeed, the products themselves will be). We may also wonder if what we are doing really has a positive impact on the world. The process by which our efforts descend to become infrastructure is really one of years (or even decades or centuries) of consistent effort. Although we often think of localization as a product of the past few decades and view it in terms of the rise of the personal computer, the earliest unambiguous example of localization in the modern sense (vs. translation, which of course goes back centuries in almost every culture) I know of is an advertisement I found browsing through an 1895 (!) copy of Scientific American, shown below:

Notice the reference to catalogs in English, French, Spanish and German near the bottom. In substance there is little to distinguish this advertisement from one published in 2003 that would advertise the availability of French, Spanish and German catalogs. Of course no one would have called these catalogs localizations in 1895 (they would have been translations, if anything), but something nearly indistinguishable from modern localization (in terms of results, if perhaps not methods) was already going on in 1895. (Unfortunately I do not have one of the catalogs, so I cannot comment on the quality of the localization.) Readers might well wonder why I mention an 1895 advertisement for industrial lathe parts in an article on the Digital Divide in India. I mention it because I think that the 1895 ad reflects the start of what we might well term a “culture of localization”—a culture that has borne fruit in the Gyandoot project and a thousand other places and projects. Starting in the late 1800s much of the world was reaching a high level of globalization (although, again, the term was not used), and some economists hold that international market integration was actually higher prior to the First World War than at any time since, including the present. Early localizations in the context of large-scale globalization contributed to a tradition and body of practice that has had an impact to this day. Collectively, although perhaps not singularly, these early localizations set the stage for what has come in later years. The Gyandoot project shows what the downstream result of such efforts can be. Although Gyandoot cannot be said in any way to depend specifically on the early localization efforts of the long-defunct Westcott Chuck Company, we can see in the 1895 ad a precedent for localization, something that helped define a future in which Gyandoot could exist. The effect of the Westcott Chuck Company’s localizations and thousands upon thousands of localizations since then, was to alter the world. Increasing amounts of localization and increasing expectations for localization have created the necessary conditions for innovative projects like Gyandoot. Just as modern computers rely on the products of 50+ years of development, much of it now obsolete, our localizations of today both rely on those of years past and make the localizations and developments of tomorrow possible, even as they are consumed in the never-ending cycle of progress. Early localizers could not have foreseen Gyandoot, yet their work helped create the conditions in which Gyandoot became technically possible, and they have, however indirectly, contributed to a project that shows all signs of delivering great benefits to its users. I would like to close with the thought that in Gyandoot we can see how the culture of localization has been brought to India, but like all culture, is being constantly redefined and reinterpreted. In other words, it is being localized.

Reprinted

by permission from the Globalization Insider,

9 September 2003, Volume XII, Issue 3.6. Copyright the Localization Industry Standards Association (Globalization Insider: www.localization.org, LISA: www.lisa.org) and S.M.P. Marketing Sarl (SMP) 2004

E-mail this article to your colleague! Need more translation jobs? Click here! Translation agencies are welcome to register here - Free! Freelance translators are welcome to register here - Free! |

|

|

Legal Disclaimer Site Map |